T>T: High-Precision Eigenvalue Computations Made Efficient in C++

The Problem

The Schrödinger equation is at the heart of quantum mechanics serving as a foundation for understanding the behavior of subatomic systems. In the context of quantum chemistry we normally solve the stationary state, time independent, non-relativistic Schrödinger equation, TISE, given by

\[\hat{H}\Psi = E\Psi.\]In most practical applications we formulate our problems as a generalised eigenvalue problem, GEP, given as

\[\mathbf{H}\Psi = \lambda\mathbf{S}\Psi,\]where \(\mathbf{H}\) represents our Hamiltonian matrix, \(\mathbf{S}\) the overlap matrix with \(\lambda\) being our energy eigenvalue. This matrix equation which is more amenable for computation may appear straightforward, however, solving it can often be very complex in practice. I have wrestled with these numerous times and have developed a toolbox of tricks to help solve them.

One of the key issues making GEPs difficult to solve is their numerical stability which can be thought of as how errors introduced during the execution of an algorithm affect the end result. There is a large variety of manipulations and tricks you can use to pre-process the input matrices or to reformulate the problem to reduce these errors but sometimes these are not enough. For anyone who has tried to calculated the eigenvalues for an excited state problem will be fully aware of these numerical difficulties…

One “last resort” solution involves increasing the computational precision from double precision (~16 digits) to quadruple precision (~32 digits). This approach is not preferred, as it is significantly slows down computation time. Quadruple precision is a non-native data type, which lacks support in nearly all programming languages where the double (or long double) data type offers the highest native precision.

How significant is the time penalty going from 16 to 32 or even 64 digit precision? This depends on the problem you are solving but can easily be 100x slower.

Is there a “least slowest” way of solving these GEP problems using quadruple, 32-digit precision in C++? In this post I will discuss one such method which I use.

The Solution

Many arbitrary precision algorithms and libraries have been developed using fixed precision arithmetic. They can be divided into two groups based on the philosophy used in how they represent numbers. Some libraries store numbers in a multiple-digit format, with a sequence of digits coupled with a single exponent, such as symbolic computation packages like Maple and Mathematica, or other very common libraries such as GNU MPFR. These are the most common tools used by scientists to achieve higher precision in their calculations but they are slow, even though they are capable of achieving arbitrary precision.

An alternative approach is to store numbers in a multiple-component format, where a number is expressed as unevaluated sums of ordinary floating-point numbers, each with its own significand and exponent. As an example consider the two expressions \(x\) and \(y\) below which are each represented as the unevaluated sum of two IEEE double precision numbers

\[\begin{aligned} x &= x_1 + x_2, \newline y &= y_1 + y_2, \end{aligned}\]Here, \(x_1, y_1\) are the leading components of their numbers \(x,y\) respectively, and \(x_2, y_2\) are the trailing component such that \(\rvert x_2 \rvert \leq \epsilon \rvert x_1 \rvert\rvert x_2 \rvert \leq \epsilon \rvert x_1 \rvert\) and \(\rvert y_2\rvert \leq \epsilon \rvert y_1 \rvert\rvert y_2 \rvert \leq \epsilon \rvert y_1 \rvert\), where \(\epsilon\) is the machine epsilon for double precision. Each subsequent component \((x_2,x_3,x_4\) etc… captures increasingly smaller parts of the number, ensuring very high precision.

For most scientific applications arbitrary precision is not required but just a small multiple of double precision (such as twice or quadruple). The algorithms for this kind of precision can be made significantly faster than those for arbitrary precision. One such library which implements this idea is the QD library developed by Bailey et al. which implements “double-double” precision, twice the double precision and “quad-double” precision, four times the double precision. These are much faster than the standard MPFR data types a lot of scientists may use when desiring higher precision. When solving these GEPs I do not need 200 digits of precision, 32 will suffice which these data types are optimised specifically for whereas the MPFR types have to work across any specified precision.

Let’s write a short code implementing these aforementioned data types. I linked to the original author’s page above for the QD library however due to the age of the code base some tweaks are required to some of the header files in order to make it work on modern architectures (if you need to know these feel free to message me). However we are in luck as there is a header only version of this repository called qdpp. This makes using the QD library much easier as there is no need to install it and the syntax is more up to date with modern C++ standards.

Next we need to select a C++ linear algebra library of which there are many. My personal favourite is Eigen as it is easily extensible to custom numeric types which other libraries lack. Another major advantage is that it can be used as a header only library so once again no installation required; we can just use the header files. Download these two libraries before continuing.

Next we import the libraries we need and setup the namespace for Eigen.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

#include <stdio.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <sstream>

#include <Eigen/Eigenvalues>

#include <mpreal.h> // header for GNU MPFR

#include <algorithm>

#include <complex>

#include <qd/qd_real.h> // header for quad-double (qd_real)

#include <qd/dd_math.h> // header for double-double (dd_real)

using namespace Eigen;

using namespace std;

Next we are going to create some templates specialized for different precision types. Read here for more information on why I love using templates.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

// define template structure for precision

template<typename T>

struct Precision;

template<>

struct Precision<dd_real> {

static constexpr int value = 32; // DoubleDouble-precision, 32-digits

};

template<>

struct Precision<qd_real> {

static constexpr int value = 64; // QuadDouble-precision, 64-digits

};

template<>

struct Precision<mpfr::mpreal> {

static constexpr int value = 32; // mpreal set to 32 digit precision for comparison with dd_real

};

Next we create our function to calculate the eigenvalues which we call CalcEigenvals. Note how we use a function template which are functions that can operate with generic types, in this example Real. This allows us to create a function template whose functionality can be adapted to more than one type or class without repeating the entire code for each type. Handy! Check out the comments for a description of what each line does

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

template <typename Real>

void CalcEigenvals(int mat_size) {

// define matrix and vector types used in code

// MatrixXz defined as Eigen matrix with generic type Real using two dimensions

// VectorXz defined as Eigen vector with generic type Real using one dimension

typedef Eigen::Matrix<Real,Dynamic,Dynamic,RowMajor> MatrixXz;

typedef Eigen::Matrix<Real,Dynamic,1> VectorXz;

// set the random seed using srand, used by Eigen to generate random matrices

// this will make the matrices the same each time for each data type

srand(42);

// generate random square matrices using Eigen specified using our custom MatrixXz type

MatrixXz lhs_mat = MatrixXz::Random(mat_size, mat_size);

srand(26);

MatrixXz rhs_mat = MatrixXz::Random(mat_size, mat_size);

// calculate eigenvalues using Eigen GEP solver

GeneralizedSelfAdjointEigenSolver<MatrixXz> es(lhs_mat, rhs_mat, EigenvaluesOnly);

VectorXz EigenvalueVec = es.eigenvalues();

// extract first eigenvalue from vector (because why not?)

Real ExtractedEigenValue = EigenvalueVec[0];

// call the precision templates so output precision matches precision of data type

cout << "\n" << setprecision(Precision<Real>::value) << ExtractedEigenValue;

}

Finally we create int main to call this function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

// catch if no matrix size is provided by the user

if (argc != 2) {

cout << "Usage: " << argv[0] << " <matrix_size>" << endl;

return 1;

}

// use command line argument to set size of matrices

int mat_size = atoi(argv[1]);

// generate eigenvalues using dd_real precision, 32 digits

CalcEigenvals<dd_real>(mat_size);

// generate eigenvalues using qd_real precision, 64 digits

CalcEigenvals<qd_real>(mat_size);

// Specify the global precision to be used (in bits) for mpreal:

// 16bit = half,

// 32bit = single,

// 64bit = double,

// 128bit = quadruple

mpfr::mpreal::set_default_prec(128);

// generate eigenvalues using mpreal precision, 32 digits

CalcEigenvals<mpfr::mpreal>(mat_size);

return 0;

}

Compiling code

To compile this code on my MacBook M1 I used the following two commands

1

2

3

g++-14 -c "dd_qd_mpfr_eigenvalues.cpp" -g -O3 -fopenmp -std=c++20 -o dd_qd_mpfr_eigenvalues.cpp.o -I/link_to_eigen_folder -I/link_to_mpfr_header_file -I/opt/homebrew/include/ -I/link_to_qdpp_folder -L/opt/homebrew/lib/ -DEIGEN_DEFAULT_DENSE_INDEX_TYPE=int

g++-14 dd_qd_mpfr_eigenvalues.cpp.o -o dd_qd_mpfr_eigenvalues -L/opt/homebrew/lib/ -lmpfr -lgmp -lm -Wl, -DEIGEN_DEFAULT_DENSE_INDEX_TYPE=int -fopenmp

We are done! This shows how easy it is to use these optimised, higher precision types as drop-in replacements for standard float or double when using the Eigen C++ library. You can run this code by calling the binary name and providing a matrix dimension.

1

dd_qd_mpfr_eigenvalues 10

and this will return the generalised eigenvalues calculated using each of the 3 data types on randomly generated matrices.

1

2

3

-3.32361249928752178695374578519557e+07 # dd_real

-3.3236124992875217869537457851945383735713881932771345078904322360e+07 # qd_real

-33236124.992875217869537457851945 # mpreal

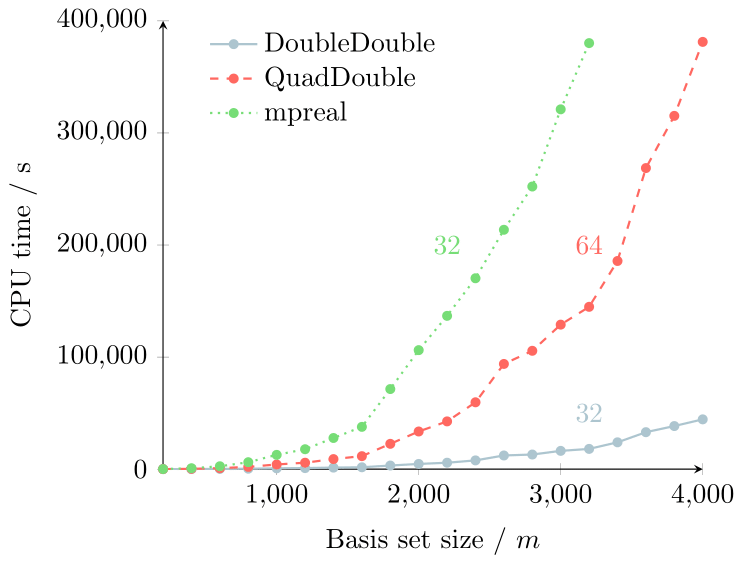

So how much faster is dd_real compared to mpreal set to 32-digit precision? The plot below shows data I calculated for the CPU time it took to calculate all the eigenvalues of the helium atom with increasing basis set size (matrix size) using a near exact numerical solution of the TISE based on an improvement on the seminal work of Pekeris.

This data was originally generated on my old iMac 4GHz Intel Quad Core i7 with 32GB 1867MHz DDR3 Memory.

This shows very clearly how much faster the dd_real data type is compared to mpreal for an equivalent 32-digit precision calculation. For a 3000 x 3000 matrix the dd_real data type is 20 times faster than the equivalent mpreal calculation and the computational scaling past a basis size of 4000 is much better for dd_real.

Even more interesting is that calculating all the eigenvalues at 64-digit precision using qd_real is faster than the mpreal 32-digit precision calculation!

Conclusion

If you require 32 or 64 digit precision for a calculation, do not use libraries which implement arbitrary precision data types such as GNU MPFR. Use the optimised operations found within the QD library which offer much better performance on the exact same calculation.

Complete code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

#include <stdio.h>

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <sstream>

#include <Eigen/Eigenvalues>

#include <mpreal.h>

#include <algorithm>

#include <complex>

#include <qd/qd_real.h>

#include <qd/dd_math.h>

using namespace Eigen;

using namespace std;

// define template structure for precision

template<typename T>

struct Precision;

template<>

struct Precision<dd_real> {

static constexpr int value = 32; // DoubleDouble-precision

};

template<>

struct Precision<qd_real> {

static constexpr int value = 64; // QuadDouble-precision

};

template<>

struct Precision<mpfr::mpreal> {

static constexpr int value = 32; // mpreal at 32 digit precision

};

template <typename Real>

void CalcEigenvals(int mat_size) {

// Define matrix and vector types used in program. Xmp ending corresponds to mpreal, Xz endings correspond to dd_Real

typedef Eigen::Matrix<Real,Dynamic,Dynamic,RowMajor> MatrixXz;

typedef Eigen::Matrix<Real,Dynamic,1> VectorXz;

// generate random square matrices

MatrixXz lhs_mat = MatrixXz::Random(mat_size, mat_size);

MatrixXz rhs_mat = MatrixXz::Random(mat_size, mat_size);

// calculate eigenvalues using Eigen

GeneralizedSelfAdjointEigenSolver<MatrixXz> es(lhs_mat, rhs_mat, EigenvaluesOnly);

VectorXz EigenvalueVec = es.eigenvalues();

// extract first eigenvalue from vector

Real ExtractedEigenValue = EigenvalueVec[0];

cout << "\n" << setprecision(Precision<Real>::value) << ExtractedEigenValue;

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

int mat_size = atoi(argv[1]);

CalcEigenvals<dd_real>(mat_size);

CalcEigenvals<qd_real>(mat_size);

// Specify the global precision to be used (in bits):

// 16bit = half,

// 32bit = single,

// 64bit = double,

// 128bit = quadruple

mpfr::mpreal::set_default_prec(128);

CalcEigenvals<mpfr::mpreal>(mat_size);

return 0;

}