T>T: Behind the Doors of the Monty Hall Puzzle

Try the code yourself!

Click the following button to launch an ipython notebook on Google Colab which implements the code developed in this post:

The Monty Hall problem poses a probability puzzle that, at first glance, appears deceptively simple but unfolds into a solution that defies intuition. Named after the host of the television game show “Let’s Make a Deal,” this problem challenges our understanding of probability. In this post, we will introduce and summarise the Monty Hall problem, explain its rules, and write a short Python code to simulate its outcomes.

The Problem

- You are a contestant on a game show.

- There are three doors in front of you. Behind one of them is a valuable prize (e.g., a car), and behind the other two are less desirable items (e.g., goats).

- You choose one of the doors, but you don’t open it just yet.

- The game show host, Monty Hall, who knows what is behind each door, opens one of the remaining two doors to reveal a less desirable item (a goat).

- Now, you have a choice: stick with your initial choice or switch to the other unopened door.

Quite frankly I would love to win a goat but for the purposes of this conversation we will assume the reader has slightly loftier aspirations than becoming the proud owner of a bleating lawn mower.

It appears counterintuitive but your best option is to switch to the unopened door. The choice masquerades as a 50:50 chance so it feels like there should be no advantage in switching doors. Even Paul Erdős one of the most prolific mathematicians working in probability theory took time to understand the solution.

Instead of delving into the mathematical details, which are available elsewhere on the internet, we’ll employ Python to compute the solution. This involves creating a simulation to model the Monty Hall problem, where we calculate the probabilities of winning under the staying and switching strategies. Taking it a step further, we’ll introduce additional doors to the problem, examining their impact on the overall probability.

First we tackle the standard Monty Hall problem with three doors which has been implemented in the monty_hall_simulation function below. The comments explain the logic behind the implementation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

from typing import Tuple

import random

def monty_hall_simulation(num_simulations: int) -> Tuple[int, int]:

"""

Run n simulations of the monty hall problem and record the number of wins

by sticking with the initial choice, or switching.

Args:

num_simulations (int): The number of games to play

Returns:

Tuple[int, int]: The number of wins when sticking and switching.

"""

stick_wins = 0

switch_wins = 0

for _ in range(num_simulations):

# simulate the initial choice

choices = ['goat', 'goat', 'car']

# shuffle the order of the choices

random.shuffle(choices)

# make a choice, i.e., select a door

initial_choice = random.choice([0, 1, 2])

# now Monty opens a door with a goat

# we need to find the doors with goats behind them so we filter out the door

# if it has the car behind it it has a goat behind it

remaining_choices = [i for i in range(3) if i != initial_choice and choices[i] == 'goat']

# pick one of these doors with a goat behind it

monty_opens = random.choice(remaining_choices)

# simulate sticking with the initial choice

stick_wins += 1 if choices[initial_choice] == 'car' else 0

# simulate switching to the other unopened door

switch_choices = [i for i in range(3) if i != initial_choice and i != monty_opens]

switch_wins += 1 if choices[switch_choices[0]] == 'car' else 0

return stick_wins, switch_wins

# set the number of Monty Hall simulations to run

num_simulations = 1000

# call the monty hall function

stick_wins, switch_wins = monty_hall_simulation(num_simulations)

print(f"Sticking with the initial choice wins {stick_wins} out of {num_simulations} times.")

print(f"Switching doors wins {switch_wins} out of {num_simulations} times.")

Running the above code for 1000 simulations produces the following output. Note that if you run the code the numbers will not be identical to these as the output is stochastic.

1

2

Sticking with the initial choice wins 340 out of 1000 times.

Switching doors wins 660 out of 1000 times.

This shows that over the course of 1000 Monty Hall simulations; switching from your initial choice after Monty Hall opens the other door almost doubles your chances of winning the car. When we switched we won 660 out of 1000 times but if we stuck with our initial choice, we only won 340 times.

This aligns numerically with the precise mathematical solution, where the probability of winning by sticking with the initial choice is 1/3, while switching doors yields a winning probability of 2/3.

Why is this the case though? The trick in understanding the Monty Hall problem is that you are given extra information about the system after your initial choice:

You have a 1/3 chance of guessing correctly on the first try. This means there is a 2/3 chance that you guessed incorrectly. Switching gives you that 2/3 chance of getting it correct.

Before Monty Hall opens a door, you have a higher chance of losing. If you are losing, then the host opens the other door, so switching means that you get the car and win.

If you are winning, then the host opens one of the goat doors, and switching means you’ll choose the other goat door and lose.

Switching will always turn a win into a loss, and a loss into a win.

You are more likely to be losing at the start so switching is more likely to turn a loss into a win than a win into a loss.

Now we are going to generalise the Month Hall problem to the case of \(n\) doors. This only involves a small change to the monty_hall_simulation function we wrote above. We need to dynamically create the car and goats behind the specified number of doors. We only have a single car so can set the list of choices using

1

choices = ['goat'] * (num_doors - 1) + ['car']

where we subtract one from the number of specified doors and create a ‘goat’ list of this length. The car is then added onto the list which means the length of the choices list is equal to the number of specified doors.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

from typing import Tuple

import random

def monty_hall_simulation(num_simulations: int, num_doors:int) -> Tuple[int, int]:

"""

Run n simulations of the monty hall problem using m doors and record the number of wins

by sticking with the initial choice, or switching.

Args:

num_simulations (int): The number of games to play

num_doors (int): The number of doors in the game

Returns:

Tuple[int, int]: The number of wins when sticking and switching.

"""

# ensure there's at least three doors

if num_doors < 3:

raise ValueError("There must be at least 3 doors for one car and two goats.")

stick_wins = 0

switch_wins = 0

for _ in range(num_simulations):

# initialize the doors with one car and (num_doors - 1) goats

choices = ['goat'] * (num_doors - 1) + ['car']

# shuffle the order of the choices

random.shuffle(choices)

# make a choice, i.e., select a door

initial_choice = random.randint(0, num_doors - 1)

# now Monty opens a door with a goat

# we need to find the doors with goats behind them so we filter out the door

# if it has the car behind it it has a goat behind it

remaining_choices = [i for i in range(num_doors) if i != initial_choice and choices[i] == 'goat']

# pick one of these doors with a goat behind it

monty_opens = random.choice(remaining_choices)

# simulate sticking with the initial choice

stick_wins += 1 if choices[initial_choice] == 'car' else 0

# simulate switching to the other unopened door

switch_choices = [i for i in range(num_doors) if i != initial_choice and i != monty_opens]

switch_wins += 1 if choices[switch_choices[0]] == 'car' else 0

return stick_wins, switch_wins

# set the number of Monty Hall simulations to run

num_simulations = 10000

# set the number of doors

num_doors = 5

# call the monty hall function

stick_wins, switch_wins = monty_hall_simulation(num_simulations, num_doors)

print(f"Sticking with the initial choice wins {stick_wins} out of {num_simulations} times.")

print(f"Switching doors wins {switch_wins} out of {num_simulations} times.")

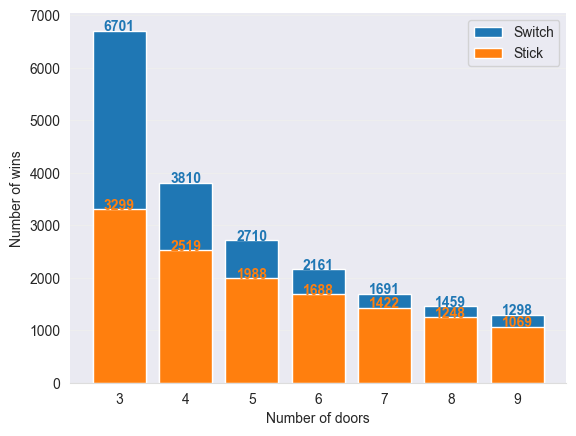

We can now run the simulation for different numbers of doors. The barplot below summarises the probabilities of winning given different numbers of doors for both the switching and sticking strategies.

These results show that it is always the best option to switch regardless of the number of doors, but the probability of winning when switching decreases as the number of doors increases, which is intuitive as there are more doors with goats behind them.

We can see that the probability of winning when sticking converges to \(1/n\) and the probability of winning when switching converges to \((n-1)/(n(n-2))\) where \(n\) is the number of doors. This is in agreement with the exact mathematical result.

Conclusion:

The Monty Hall problem appears deceptively simple, yet its solution is slightly more profound than one may first think. The conversation around this problem is normally centred around the mathematicla and statistical derivation but in this post we used Python to simulate and explore the problem, demonstrating that switching doors increases the chances of winning regardless of the number of doors to be opened.

The code is available through colab using the link at the top of this post, or just copy and paste it wherever you fancy. Feel free to play around with it; adjust the number of simulations, doors or add in a different situation where \(k\) doors are opened by Monty Hall or even add two prizes.